Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

This is the 7th post about our wonderful trip to northern India in November 2019. The custom tour was arranged by Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel, who arranged an itinerary, accommodation, transport and guides to our specification, which combined wildlife viewing and cultural highlights.

This post covers our half-day visit to the city of Jodhpur and a visit to some nearby villages belonging to the Bishnoi people.

After visiting Mumbar gardens (see post 6) we entered the city of Jodhpur and stopped at the Clock Tower where there was an extensive market …

… selling a wonderful variety of fruit, vegetables, clothing etc. We were able to buy some spices and masala tea, far better souvenirs than the usual tourist junk.

The whole area is overshadowed by the Mehrangarh or Mehran Fort. which dominates the skyline.

Later we were taken to our hotel, the lovely Rattan Villas near the city centre.

No dancers this time, but a musician playing traditional instruments made up for that.

The next morning we drove with a guide to Jaswant Thada, a marble mausoleum overlooking the city. Note the ancient city walls running along the skyline.

An adjacent lake got me my first Ferruginous Ducks for the trip, but the main focus was the beautiful architecture of the mauseleum.

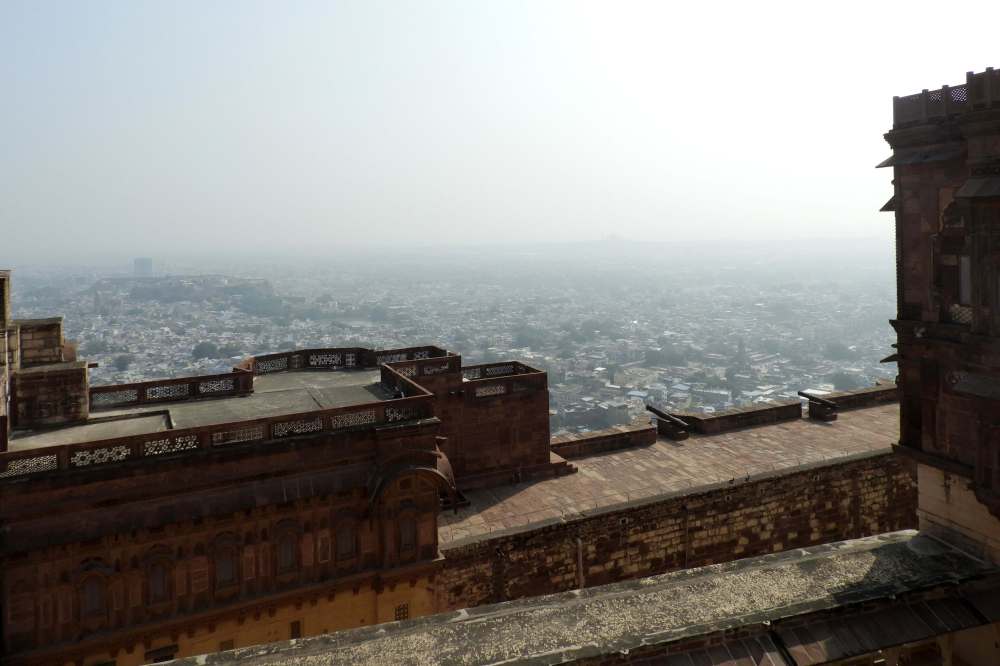

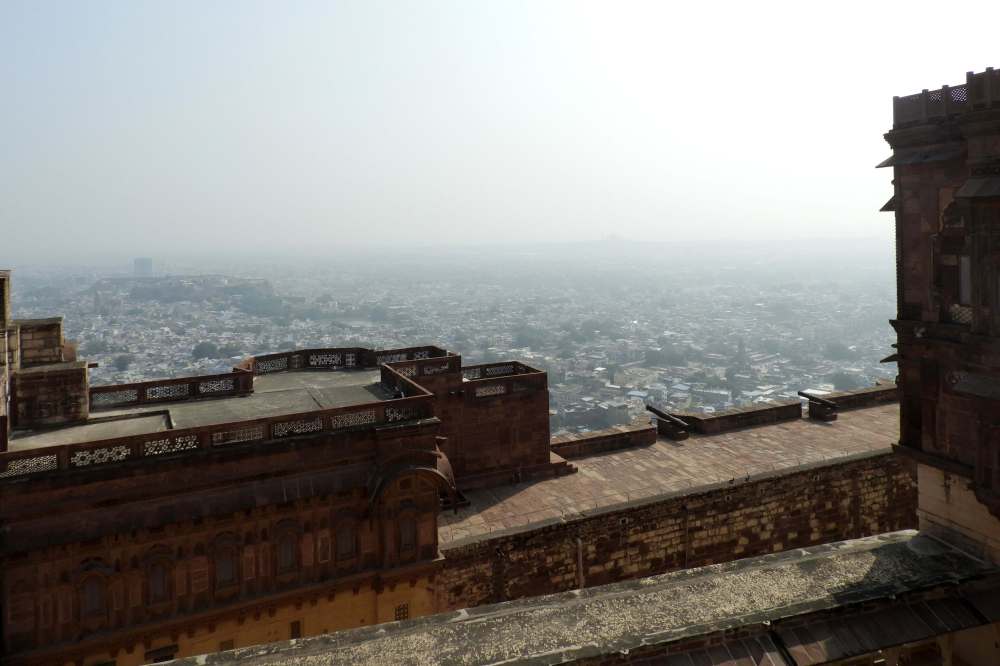

Unfortunately the usual mist and pollution haze hung over the city, but even so the view was spectacular.

Regular readers of this blog will know I’m no fan of the selfie craze, but even so I found this sign quite amusing.

From Wikipedia: The Jaswant Thada is a cenotaph located in Jodhpur, in the Indian state of Rajasthan. It was built by Maharaja Sardar Singh of Jodhpur State in 1899 in memory of his father, Mahara-ja Jaswant Singh II, and serves as the cremation ground for the royal family of Marwar.

The mausoleum is built out of intricately carved sheets of marble. These sheets are extremely thin and polished so that they emit a warm glow when illuminated by the Sun.

The cenotaph of Maharaja Jaswant Singh displays portraits of the rulers and Maharajas of Jodhpur.

The cenotaph’s grounds feature carved gazebos, a tiered garden, and a small lake. There are three other cenotaphs in the grounds.

The view from the mausoleum’s gardens were once again dominated by the Mehrangarh Fort, which was to be our next destination.

From Wikipedia says about the Mehrangarh Fort,: There are seven gates, which include Jayapol (meaning ‘victory gate’), built by Maharaja Man Singh to commemorate his victories over Jaipur and Bikaner armies. There is also a Fattehpol (also meaning ‘victory gate’), which commemorates Maharaja Ajit Singhji victory over Mughals.

The fort is truly enormous, said to be one of the largest in India.

If Jaipur is known as the pink city then Jodhpur is the blue city.

From Wikipedia (again): Jodhpur is the second-largest city in the Indian state of Rajasthan and officially the second metropolitan city of the state with a population surpassing 1.5 million. It was formerly the seat of the princely state of Jodhpur State. Jodhpur was historically the capital of the Kingdom of Marwar, which is now part of Rajasthan. Jodhpur is a popular tourist destination, featuring many palaces, forts, and temples, set in the stark landscape of the Thar Desert. It is popularly known as the “Blue City” among people of Rajasthan and all over India. It serves as the administrative headquarters of the Jodhpur district and Jodhpur division.

The old city circles the Mehrangarh Fort and is bounded by a wall with several gates. The city has expanded greatly outside the wall, though, over the past several decades

This bronze model shows the size and scale of the gigantic fort.

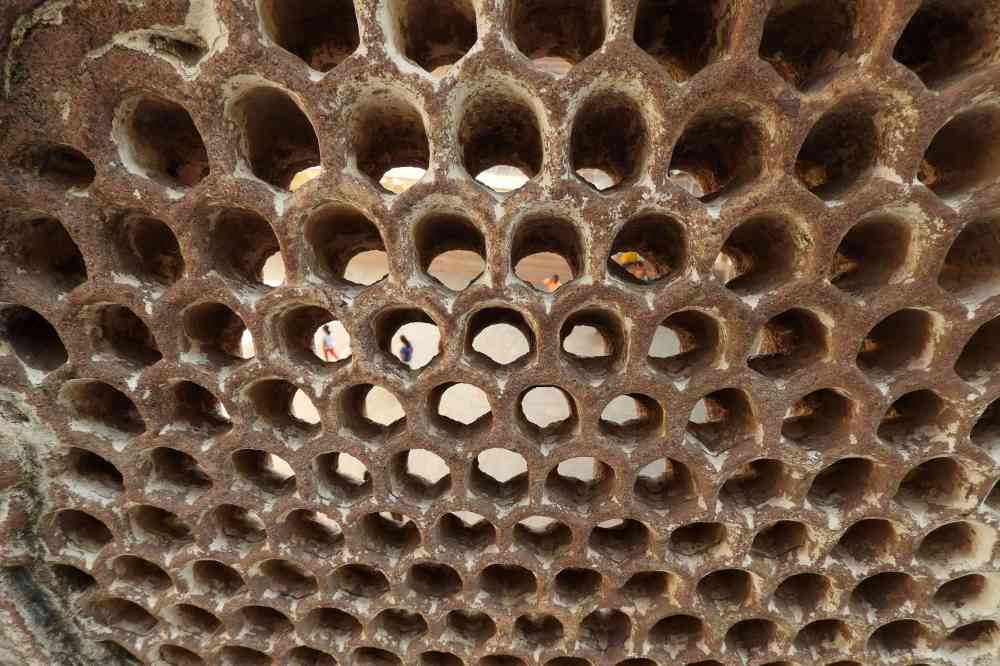

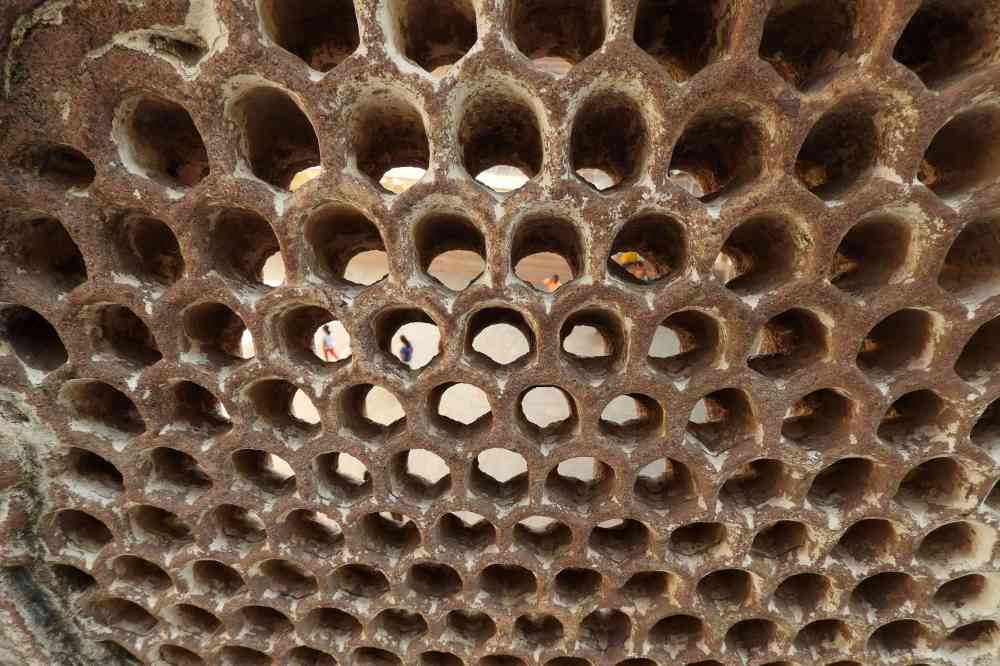

These next three photos …

shown the scale and extent of the wonderful architecture …

… and the incredibly intricate stonework seen here …

… and here.

The museum in the Mehrangarh fort is one of the most well-stocked museums in Rajasthan. In one section of the fort museum, there is a selection of old royal palanquins, including the elaborate domed gilt Mahadol palanquin which was won in a battle from the Governor of Gujarat in 1730.

The museum exhibits the heritage of former times …

… in shrines, costumes …

… paintings and decorated tapestries.

A few more photos of the fabulous interior …

… it was so gob-smackingly beautiful …

… that I failed to take in all the details that our guide was providing.

Eventually we emerged outside for another view over the city.

You get the feeling that this passage way was designed for a smaller person!

More of the delicate stonework that allows the breeze to enter but allows the women of the court to view the plazas below without being seen themselves.

This time a view complete with Rock Pigeons. The question of what is a truly wild Rock Pigeon and what is a domesticated feral pigeon is a vexed one. Certainly those in European cities and any in the New World are feral but these here on the forts of India showed every characteristic of being wild; no enlarged cere, no variation in plumage and pale grey not white rumps.

More views of the city walls …

… more highly decorated corridors …

… and yet more intricate stone work.

Later on we returned to Jodhpur and after some lunch we headed into the countryside to visit the villages of the Bishnoi people.

After lunch the guide and our driver Mehaz took us to some villages of the Bishnoi people. Apparently Bishnoi means 29 in the local dialect which comes from the 29 commandments given to members of the Bishnoi sect by Guru Jambheshwar (1451-1536). As well as religious instructions and social rules the commandments list a number of environmental considerations and instructions for sustainable living. If only Moses had thought to bring another 19 commandments with him when he descended from Mount Sinai then the world would be a very different place today! Like so many of these village tours it was really just an opportunity to sell artefacts to tourists, but the villagers seemed so much more deserving than their city counterparts (and prices were much lower).

In this rather scruffy yard we were shown how the villages make and fire the large earthenware pots and we bought a ‘terracotta sun face’ to put on our garden fence …

… whilst elsewhere and an old man with a gammy leg offered us some opium – which we politely declined.

Although we usually hate being taken to ‘carpet outlets’ when on a tour we rather stumbled on this one and as he didn’t give us the hard sell, we bought a small rug off him.

Our visit to a group of nomadic ‘snake charmers’ was more impromptu but we were welcomed in once they realised that the guide came from the same village as they did.

… although a small child ran away screaming in terror when he saw our white faces (he calmed down later for this photo).

These are the cow-turd piles that the villages construct as the fuel store for cooking and heating.

The Bishnoi believe in protecting nature and we were taken to a lake where they feed the Demoiselle Cranes that come from Central Asia for the winter. The birds were rather distant for photos so I’ve included a shot from the similar, but much larger feeding station at Bikiner some distance to the west, where the cranes can be found in their tens of thousands.

We returned to the hotel that evening but the following day was worst of the trip. The flight to Delhi was in the early afternoon which would have given us time to do some sightseeing on arrival, so in the morning we had a bit of a lie in followed by another visit to the Clock Tower markets (where once again Margaret would be asked to pose for a selfie with the locals). Then we headed to the airport in the late morning and said our goodbyes to the very capable driver Mehaz. Before we left he reminded us of the three requirements for driving in India – a good horn, good brakes and good luck! Once through security we found there was a major delay with the flight and we spent six or more hours in a tiny departure lounge that was hot, crowded and very noisy due to a loud security scanner and lots of babies. We finally arrived at our hotel in Delhi late in the evening where decided to skip dinner and get straight to bed. It was the only hiccup of the trip and completely outside the organiser’s control.

I’ll conclude with a photo of the wonderful Jaswant Thada taken with on a telephoto setting from the fort of Mehrangarh.

The eighth and final post will deal with our time at the wildlife reserve of Sultanpur Jheel near Delhi and some of the monuments within the city itself.

This is the 6th post on our wonderful trip to northern India in November 2019. The custom tour was arranged by Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel who arranged an itinerary, accommodation, transport and guides to our specification that combined wildlife viewing and cultural highlights.

After spending a day touring historic sites in Jaipur it was the turn to do some birding in the reserve of Tal Chhapar (yes that is the correct spelling!) a reserve near the village of Chhapar which is just under half way between Jaipur and the Pakistan border.

We were relatively close to Tal Chhapar on my Birdquest Western India trip in 2016 when we visited Bikaner, (as so often happens it was added to the itinerary the following year). There were two lifers for me here, one mammalian and one avian, the beautiful Blackbuck and the little-known Indian Spotted Creeper.

It was a 215 km drive from Jaipur and took over four hours. The village of Chhapar was quite unremarkable with a single busy main street and a few back streets like this.

We stayed at Raptors Inn, a private guest house run by local bird guide Atul Gurjar and his wife Sunita. They made us very welcome and provided great food. Margaret was very taken by this home stay and had a chance to ask Atul and Sunita about many aspects of Indian life including their cuisine. See more here

They tried their best to keep their boisterous children away from us but we found them most entertaining.

That afternoon we headed to a ‘gaushala’ a walled off area where the sacred cattle can safely graze. On route we passed this camel and buggy. There is clearly no law about using your phone whilst driving a camel in India! Here we were to search for the ‘semi-mythical’ Indian Spotted Creeper. Now I can’t say that I’ve been waiting to see this species all my life, I didn’t even know about of it until after it was split from its African cousin in the late 90s, but I have been wanting to see the area’s other attraction, the beautiful Blackbuck since I was a small child.

Finding the Indian Spotted Creeper took some time but there was no problem with seeing Blackbuck, up to 50 were on view. The females ,which are smaller, brown and white and have no horns were present but elusive, but the males were in rut and were bold and approachable.

Males would approach each other and then ‘parallel walk’, sizing each other up …

… sometimes disputes were resolved by this but often it ended up with an all out battle.

In due course Atul found a Spotted Creeper but it was in a line of trees by the gaushala wall. After a brief view and one very mediocre photo, it flew to some trees outside the gaushala where it could be seen but not photographed (there was a considerable drop on the other side of the wall so climbing over was impractical).

This was my first bird lifer on the tour and I was pretty pleased at this moment. This species and its African cousin are members of the Sittidae, the Nuthatch Family rather than Certhidae which contains all the (Holarctic/Oriental) treecreepers. Both photos by Prasad Natarajan see here

I think I said in an earlier post, when discussing the catastrophic decline in Indian vultures, that the only vulture we saw on the trip was Egyptian. That’s not quite true as we saw a single wintering Eurasian Griffon Vulture. How ever that doesn’t detract from my earlier statement that because of poisoning, the formerly widespread and abundant Slender-billed, White-rumped and Indian Vultures are now critically endangered.

Other raptors included this Black-winged Kite …

… and a beautiful Long-legged Buzzard.

Other birds photographed that afternoon included the punk-crested Brahminy Starling (above) and …

… flocks of Indian Silverbills, small estridid finches, native to India but introduced to many other places.

There were a few ‘lesser whitethroats’ wintering. The taxonomy of this group has been controversial with between one and five species accepted at various times and by various authorities. IOC and HBW both now recognise three species, Hume’s Whitethroat which breeds in the mountains of Central Asia and winters in southern Baluchistan and SW India, Lesser Whitethroat which breeds from western Europe to east-central Siberia and winters in Africa and northern India and Desert Whitethroat which breeds in parts of China and Turkestan and winters in the Arabian peninsular and north-west India. This bird is a classic minula, ie a Desert Lesser Whitethroat, small, sandy with reduced grey in the crown.

There were quite a few Lanius shrikes in the area, including this male Bay-backed, which looks like a Penduline Tit on steroids …

… and the more familiar Great Grey Shrike, although here of the race archeri. The ‘great grey shrike’ group has undergone a lot a changes during the last few decades. Originally one species, then three (Southern, Great Grey and Steppe), its now still three but a different three: Northern Grey occurs in North America and eastern Siberia, Iberian Grey occurs where it’s name suggests and all the rest are re-lumped in Great Grey again. The problem seems to be that genetics and morphology don’t match, maybe eventually more sensitive and innovative genetic methods will be able to divide this group further and so better match DNA to plumage.

Also present were a number of Common Woodshrikes. These are not related to true shrikes of the genus Lanius (see the two photos above) but instead are members of the Vangidae, an unusual Family which includes the vangas of Madagascar, the African helmetshrikes and shrike-flycatchers and Asian philentomas.

After we had our meal that evening we heard very loud music coming down the street. Atul and Sunita said it was a pre-wedding celebration, so we decided to take a look.

Although they had never met us before the villagers were most welcoming. First they brought chairs out into the street so we could watch the dancing in comfort, then they invited us into their house and where the ladies were keen to be photographed with Margaret.

Later we (well mainly Margaret) joined in with the dancing …

… and we were treated as honoured guests. The bride and groom-to-be had yet to arrive but everyone else seemed to be having a great time on their behalf.

Now I’ve heard of ‘a bull in a china shop’ but its not that often that you come across the ‘cow at the mobile disco’, well not this sort of cow anyway.

Atul was a bit hesitant about visiting the actual Tal Chappar reserve (Tal meaning low-lying land) as heavy rain had made the tracks unsuitable for vehicles. As a result the following morning we first visited a lake near the gaushala.

We found a few waterbirds we had seen earlier on like these Indian Spotbills but the River Terns we found were new for the trip.

Spotbill used to be a single species but has since been split into Indian and Chinese varieties. I think it looks rather splendid in the pale-yellow light of dawn

Eventually Atul relented and took us to the nearby Tal Chhapar, but we had to leave the vehicle at the entrance gate. In this low-lying hollow the mist persisted, producing some atmospheric views of the local Blackbuck.

As well as Blackbuck there were quite large numbers of Wild Boar.

However some of the piglets showed characteristics more typical of domestic pigs so there must be some interbreeding. Also seen were Common Cranes and Western Marsh Harriers, but unfortunately not Monties or Hen Harriers (I dare say we would have seen more if we could have stayed or if the visibility had been better).

Well we weren’t able to walk very far as we had huge great clods of mud stuck to our boots, making walking rather difficult. Back at vehicle we had a very close encounter with a male Blackbuck. I don’t know if I’ll ever see this magnificent antelope again, but if I don’t I can’t complain about the views we had this time.

So we returned to the other side of the road and explored another area dodging great herds of goats on route.

Here we found Indian Desert Jirds. We only saw about ten but their burrows were everywhere.

These little rodents are preyed on by many raptors including …

… Booted Eagles (although in Europe rabbits are their favoured mammalian prey) …

… and Long-legged Buzzard.

Tawny Eagles are know to be mainly a scavenger and a kleptoparasite but I dare say the odd Jird or two would make a tasty snack, if they were quick enough to catch one.

We had spectacular views of a Tawny Eagle being harassed by a pair of Lagger Falcons. Unfortunately in my photos either the eagle or falcon are blurred so I’ve included one from iNaturalist taken by Philippe Boissel see here

The little Shikra is in the genus Accipiter which feeds mainly on birds rather than rodents.

Rather commoner than the larger Gyps vultures but still declining severely is the widespread Egyptian Vultures.

We came across a group of four on our drive around.

Also seen was (yet another) Spotted Owlet.

Enjoyable as it had been it was time to leave Chhapar and heard to our next destination.

That afternoon we drove to Jodhpur and stopped for a short while at Mumbar Gardens near the city where there was an attractive temple and a wetland area caused by the damming of the local river.

We didn’t learn anything about the temple a this was just a short impromptu stop …

… but like all old Indian architecture it was very beautiful.

There were a few birds in the temple area …

… but most were in the overgrown water channel. These included a ‘water rail’, I hoped that it would be the recently split Eastern Water Rail (or Brown-cheeked Rail), after all the scientific name is Rallus indicus, but it proved to be the same one we get at home.

Perhaps the most notable feature of the temple was the very approachable Hanuman Langurs.

The next post will cover our visit to the city of Jodhpur, the nearby Bishnoi villages and a nearby lake where Demoiselle Cranes gather.

This post covers our stay in the city of Jaipur, Rajasthan in northern India. This was part of a custom tour arranged by Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel which combined wildlife viewing and cultural highlights in a way that wouldn’t be possible in standard tour of India.

As I explained in the last post our bird guide at Baratphur came with us to Jaipur on 25th November as there was a site nearby where we might encounter the seldom seen Indian Spotted Creeper, but we weren’t in luck. We dropped the guide off at a bus station to get back to Bharatpur and we were taken to our hotel.

The hotels and lodges we had stayed at so far had been really good but the Umaid Mahal hotel was something special …

… with it’s highly decorated corridors …

… and a lovely room.

In the dining room we were entertained by some Indian music and dance.

The following morning we picked up our guide and drove into the centre of Jaipur.

From Wikipedia: Jaipur is the capital and the largest city of the Indian state of Rajasthan. As of 2011, the city had a population of 3.1 million, making it the tenth most populous city in the country. Jaipur is also known as the Pink City, due to the dominant colour scheme of its buildings. It is located 268 km from the national capital New Delhi.

We stopped on a busy road to photograph the Palace of Wind. Unfortunately we couldn’t get further away from the façade to take the photo so the following image shows a bad case of ‘falling over backwards’.

From Wikipedia: Hawa Mahal (English translation: “The Palace of Winds” or “The Palace of Breeze”) is a palace in Jaipur, India approximately 300 kilometres from the capital city of Delhi. Built from red and pink sandstone, the palace sits on the edge of the City Palace, Jaipur, and extends to the Zenana, or women’s chambers. The structure was built in 1799 by Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh, the grandson of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh, who was the founder of Jaipur. He was so inspired by the unique structure of Khetri Mahal that he built this grand and historical palace. It was designed by Lal Chand Ustad. Its five floor exterior is akin to honeycomb with its 953 small windows called Jharokhas decorated with intricate latticework. The original intent of the lattice design was to allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen, since they had to obey the strict rules of “purdah”, which forbade them from appearing in public without face coverings. This architectural feature also allowed cool air from the Venturi effect to pass through, thus making the whole area more pleasant during the high temperatures in summer. Many people see the Hawa Mahal from the street view and think it is the front of the palace, but it is the back. In 2006, renovation works on the Mahal were undertaken, after a gap of 50 years, to give a facelift to the monument at an estimated cost of Rs 4.568 million.[6] The corporate sector lent a hand to preserve the historical monuments of Jaipur and the Unit Trust of India has adopted Hawa Mahal to maintain it.[7] The palace is an extended part of a huge complex. The stone-carved screens, small casements, and arched roofs are some of the features of this popular tourist spot. The monument also has delicately modelled hanging cornices.

But our main focus for the day was the huge Amer Fort, which is usually known as the Amber Fort.

We parked and climbed up the access road which gave us views of the modern town and and the ancient walls that enclosed the town and fort. Some of the wall can be seen just to the right of the large cream-coloured buildings in the upper right of the photo.

There was a lot of step climbing involved.

Some views over the town from the fort – here …

… and also here. More of the wall can be seen in the upper right corner.

Some people opt for an elephant ride around the lower part of the fort but we didn’t bother.

It was quite spectacular to watch the procession of elephants coming through the arch. Yet more of the ancient wall is visible through the arch …

… and in this photo. Climbing up further we visited the parts that elephants couldn’t reach.

From Wilipedia: Mughal architecture greatly influenced the architectural style of several buildings of the fort. Constructed of red sandstone and marble, the attractive, opulent palace is laid out on four levels, each with a courtyard. It consists of the Diwan-e-Aam, or “Hall of Public Audience”, the Diwan-e-Khas, or “Hall of Private Audience”, the Sheesh Mahal (mirror palace), or Jai Mandir, and the Sukh Niwas where a cool climate is artificially created by winds that blow over a water cascade within the palace. Hence, the Amer Fort is also popularly known as the Amer Pal-ace. The palace was the residence of the Rajput Maharajas and their families. At the entrance to the palace near the fort’s Ganesh Gate, there is a temple dedicated to Shila Devi, a goddess of the Chaitanya cult, which was given to Raja Man Singh when he defeated the Raja of Jessore, Bengal in 1604.

Incredibly fine ‘filigree’ stone work was employed to produce these screens, to allow maximum ventilation whilst providing the women of the court (who were not allowed to mix with outsiders) the opportunity of watching proceedings in the plaza below.

It was hard to take in or remember the function of each of the architectural marvels that we encountered …

… so may of the wonderful buildings will have to remain undescribed.

Today was a day for enjoying ancient architecture and Mogul art rather than birding, but I did have my bins with me. A large raptor that I never got to identify and some distant ducks on the lake below was about all I recorded.

More from Wikipedia: Amer Fort is a fort located in Amer, Rajasthan, India. Amer is a town with an area of 4 square kilometres located 11 kilometres from Jaipur, the capital of Rajasthan. Located high on a hill, it is the principal tourist attraction in Jaipur. The town of Amer was originally built by Meenas, and later it was ruled by Raja Man Singh I. Amer Fort is known for its artistic style elements. With its large ramparts and series of gates and cobbled paths, the fort overlooks Maota Lake, which is the main source of water for the Amer Palace.

Even the cleaning staff wear beautiful uniforms!

Within the palace were wonderful floral frescos …

… and pretty gardens.

Much of the decoration consisted of intricate patterns on the walls and ceilings. This ceiling has a series of small mirrors set in it …

… evidenced by the fact that in the mirror just left of centre, you can see part of my arm and camera!

I was going to include a Mogul painting of a naked man and woman painted above an entrance arch but it was so explicit that looked like an image from the Kama Sutra. However I decided that I didn’t want to get in trouble with the ‘cyber police’ and thought it wise to omit it.

On the way back into Jaipur we stopped briefly at the Water Palace or Jal Mahal. From Wikipedia (again): The Jal Mahal palace is an architectural showcase of the Rajput style of architecture (common in Rajasthan) on a grand scale. The building has a picturesque view of the lake itself but owing to its seclusion from land is equally the focus of a viewpoint from the Man Sagar Dam on the eastern side of the lake in front of the backdrop of the surrounding Nahargarh (“tiger-abode”) hills. The palace, built in red sandstone, is a five-storied building, of which four floors remain underwater when the lake is full and the top floor is exposed. One rectangular Chhatri on the roof is of the Bengal type. The chhatris on the four corners are octagonal. The palace had suffered subsidence in the past and also partial seepage (plasterwork and wall damage equivalent to rising damp) because of waterlogging, which have been repaired under a restoration project of the Government of Rajasthan.

We carried on to Jantar Mantar …

… a sort of astronomical observatory built by the Rajput King Sawai Jai Singh II in 1734.

Most of the instruments are designed to tell the time of day from the angle of the sun …

… and considerable effort was made to take account of the sun’s position at various times of the year. With a correction factor for the deviation of Jaipur from the meridian of India’s time zone applied, the result was accurate to a minute or two.

Not content with that Sawai Jai Singh II had a truly stupendous sundial built 27 m tall …

At this scale the sun’s shadow moves along the dial at 1mm per second. These are just two of nineteen instruments in the complex all built on the orders of this most scientifically minded king. As always Wikipedia is my source of information: The observatory consists of nineteen instruments for measuring time, predicting eclipses, tracking location of major stars as the earth orbits around the sun, ascertaining the declinations of planets, and determining the celestial altitudes and related ephemerides. The instruments are (alphabetical) 1. Chakra Yantra (four semicircular arcs on which a gnomon casts a shadow, thereby giving the declination of the Sun at four specified times of the day. This data corresponds to noon at four observatories around the world (Greenwich in UK, Zurich in Switzerland, Notke in Japan and Saitchen in the Pacific); this is equivalent of a wall of clocks registering local times in different parts of the world.) 2. Dakshin Bhitti Yantra (measures meridian, altitude and zenith distances of celestial bodies) 3. Digamsha Yantra (a pillar in the middle of two concentric outer circles, used to measure azimuth of the sun and to calculate the time of sunrise and sunset forecasts) 4. Disha Yantra 5. Dhruva Darshak Pattika (observe and find the location of pole star with respect to other celestial bodies) 6. Jai Prakash Yantra (two hemispherical bowl-based sundials with marked marble slabs that map inverted images of sky and allow the observer to move inside the instrument; measures altitudes, azimuths, hour angles, and declinations) 7. Kapali Yantra (measures coordinates of celestial bodies in azimuth and equatorial systems; any point in sky can be visually transformed from one coordinate system to another) 8. Kanali Yantra 9. Kranti Vritta Yantra (measures longitude and latitude of celestial bodies) 10. Laghu Samrat Yantra (the smaller sundial at the monument, inclined at 27 degrees, to measure time, albeit less accurately than Vrihat Samrat Yantra) 11. Misra Yantra (meaning mixed instrument, it is a compilation of five different instruments) 12. Nadi Valaya Yantra (two sundials on different faces of the instrument, the two faces representing north and south hemispheres; measuring the time to an accuracy of less than a minute) 13. Palbha Yantra 14. Rama Yantra (an upright building used to find the altitude and the azimuth of the sun) 15. Rashi Valaya Yantra (12 gnomon dials that measure ecliptic coordinates of stars, planets and all 12 constellation systems) 16. Shastansh Yantra (next to Vrihat Samrat Yantra) This instrument has a 60-degree arc built in the meridian plane within a dark chamber. At noon, the sun’s pinhole image falls on a scale below enabling the observer to measure the zenith distance, declination, and the diameter of the Sun.) 17. Unnatamsa Yantra (a metal ring divided into four segments by horizontal and vertical lines, with a hole in the middle; the position and orientation of the instrument allows measurement of the altitude of celestial bodies) 18. Vrihat Samrat Yantra (world’s largest gnomon sundial, measures time in intervals of 2 seconds using shadow cast from the sunlight) 19. Yantra Raj Yantra (a 2.43-metre bronze astrolabe, one of the largest in the world, used only once a year, calculates the Hindu calendar) The Vrihat Samrat Yantra, which means the “great king of instruments”, is 88 feet (27 m) high; its shadow tells the time of day. Its face is angled at 27 degrees, the latitude of Jaipur. The Hindu chhatri (small cupola) on top is used as a platform for announcing eclipses and the arrival of monsoons. Jai Prakash Yantra at Jantar Mantar, Jaipur The instruments are in most cases huge structures. The scale to which they have been built has been alleged to increase their accuracy. However, the penumbra of the sun can be as wide as 30 mm, making the 1mm increments of the Samrat Yantra sundial devoid of any practical significance. Additionally, the masons constructing the instruments had insufficient experience with construction of this scale, and subsidence of the foundations has subsequently misaligned them. The samrat yantra, for instance, which is a sundial, can be used to tell the time to an accuracy of about two seconds in Jaipur local time.[13] The Giant Sundial, known as the Samrat Yantra (The Supreme Instrument) is one of the world’s largest sundials, standing 27 metres tall.[14] Its shadow moves visibly at 1 mm per second, or roughly a hand’s breadth (6 cm) every minute, which can be a profound experience to watch.

We continued with an obligatory visit to carpet makers, but we convinced our guide we didn’t want to stop long (unlike our experiences in Turkey and UAE).

The final stop on our guided tour was the City Palace within the city of Jaipur.

And yet more from Wikipedia:The City Palace, Jaipur was established at the same time as the city of Jaipur, by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, who moved his court to Jaipur from Amber, in 1727. Jaipur is the present-day capital of the state of Rajasthan, and until 1949 the City Palace was the ceremonial and administrative seat of the Maharaja of Jaipur. The Palace was also the location of religious and cultural events, as well as a patron of arts, commerce, and industry. It now houses the Mahara-ja Sawai Man Singh II Museum, and continues to be the home of the Jaipur royal family. The royal family of Jaipur is said to be the descendants of Lord Rama. The palace complex has several buildings, various courtyards, galleries, restaurants, and offices of the Museum Trust. The Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust looks after the Museum, and the royal cenotaphs (known as chhatris).

Once more we saw some exquisite architecture …

… and beautiful buildings.

Of particular note was a quadrangle with four large ornate doors representing the four seasons.

… here are close ups of the arches above the other three doors, although which one represents which season …

…. is rather hard to tell …

… but that doesn’t detract from their beauty.

A few more images of the City Palace …

… Margaret posed for a photo with these guards …

… before we left to find our vehicle.

Our guide departed and we spent the last hour of the day looking around some shops …

… away from the tourist areas.

Unlike similar places in other parts of Asia or north Africa there was no hassle …

… and you could take your time wandering around. We were able to buy a few Christmas gifts for the family.

The food markets were most colourful …

… and Margaret stocked up on a few goodies for the journey tomorrow.

So it was back to our lovely hotel …

… where that evening the dancers played the ‘how many pots can I balance on my head’ game. Later the two dancers got people at tables to get up and dance with them. Margaret of course joined in, I have some video of the event but unfortunately no still photos.

The following day we left the city and headed to the small town of Tal Chhapar. Although I had seen a lifer mammal (Sloth Bear) on the trip I had not added any birds to my life list. But one was waiting, I hoped, in a reserve just outside Tal Chhapar. This will be the subject of the next post.

This is the fourth post on our trip to India in 2019. We wanted a mixture of watching wildlife and cultural sites, a combination that isn’t easy to find on most commercial tour. The trip arranged by Jo Thomas at Wild About Travel was to our specifications and perfectly combined India’s wonderful temples, ancient buildings and unique way of life with watching Tigers, Blackbucks and loads of birds.

This post covers one of the most famous wildlife reserves in the world, officially called the Keoladeo National Park but universally known by the name of the adjacent city – Bharatpur.

To save me typing it here is the description of the reserve from Wikipedia: Keoladeo National Park or Keoladeo Ghana National Park formerly known as the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India is a famous avifauna sanctuary that hosts thousands of birds, especially during the winter season. Over 230 species of birds are known to be resident. It is also a major tourist centre with scores of ornithologists arriving here in the winter season. It was declared a protected sanctuary in 1971. It is also a World Heritage Site. Keoladeo Ghana National Park is a man-made and man-managed wetland and one of the national parks of India. The reserve protects Bharatpur from frequent floods, provides grazing grounds for village cattle, and earlier was primarily used as a waterfowl hunting ground. The 29 km2 reserve is locally known as Ghana, and is a mosaic of dry grasslands, woodlands, woodland swamps and wetlands. These diverse habitats are home to 366 bird species, 379 floral species, 50 species of fish, 13 species of snakes, 5 species of lizards, 7 amphibian species, 7 turtle species and a variety of other invertebrates. Every year thousands of migratory waterfowl visit the park for wintering and breeding. The sanctuary is one of the richest bird areas in the world and is known for nesting of resident birds and visiting migratory birds including water birds. The rare Siberian cranes used to winter in this park but this central population is now extinct. According to founder of the World Wildlife Fund Peter Scott, Keoladeo National Park is one of the world’s best bird areas.

Again from Wikipedia: The sanctuary was created 250 years ago and is named after a Keoladeo (Shiva) temple within its boundaries. (see photo above). Initially, it was a natural depression; and was flooded after the Ajan Bund was constructed by Maharaja Suraj Mal, then the ruler of the princely state of Bharatpur, between 1726–1763. The bund was created at the confluence of two rivers, the Gambhir and Banganga. The park was a hunting ground for the Maharajas of Bharatpur, a tradition dating back to 1850, and duck shoots were organised yearly in honour of the British viceroys. In one shoot alone in 1938, over 4,273 birds such as mallards and teals were killed by Lord Linlithgow, then Viceroy of India.[citation needed] The park was established as a national park on 10 March 1982. Previously the private duck shooting preserve of the Maharaja of Bharatpur since the 1850s, the area was designated as a bird sanctuary on 13 March 1976 and a Ramsar site under the Wetland Convention in October 1981. The last big shoot was held in 1964 but the Maharajah retained shooting rights until 1972. In 1985, the Park was declared a World Heritage Site under the World Heritage Convention. It is a reserve forest under the Rajasthan Forest Act, 1953 and therefore, is the property of the State of Rajasthan of the Indian Union. In 1982, grazing was banned in the park, leading to violent clashes between local farmers and the government.

During the days of the Raj the site was renowned as a great place for shooting wildfowl. Looking at this tally board that’s still on display it was possible to shoot many thousands of birds in a single day. Of course due to the widespread destruction of breeding sites throughout Asia there are nowhere near as many birds visiting as in the past but a visit to ‘Bharaptpur’ still remains one of the world’s top birding experiences. I don’t like the shooting of wildfowl but it would be fair to say that the reserve probably wouldn’t be in its current state without the patronage of shooters in years gone by.

I visited Bharatpur before in 1986 and at that time it was one of the best birding experiences of my life. We were there for nearly three days compared to a day and a half this time and saw a truly awesome number of birds. By the time 2019 had come around it was highly unlikely that I would get any ‘life birds’ at the site but I wanted Margaret to experience it’s avian richness and of course enjoy it myself.

Our journey from the hotel to the park and around the park itself was by bicycle rickshaw with our bird guide cycling along beside. In true Indian fashion we were taken the wrong way down a duel carriageway!

Once in the park you realise that you’re not the only one using a bicycle rickshaw. Most of the rest of this quite extensive post is a collection of bird and other wildlife photos interspersed with a few habitat shots and there is only a limited amount I can say about each.

One of the first species encountered is one I know well from home, indeed it even occurs in my garden. Originally confined to the Orient and Middle East Eurasian Collared Doves expanded its range rapidly in the 20th century spreading across Europe and reaching the UK in the late 50s. It soon became a common bird in towns and gardens. Soon afterwards some Collared Doves either escaped or were released in the Bahamas and rapidly spread to the USA where they are now common (I believe) from coast to coast.

Along the central track we saw these Grey Francolins.

I have shown a few photos of Jungle Babblers on earlier posts, here we saw their cousins Large Grey Babblers …

… which as you have probably realised are a bit larger and a bit greyer.

As with several other sites we visited Spotted Owlets were easy to see at their daytime roost.

They could be seen indulging in a bit of mutual preening, so-called allopreening.

There were several colonies of Indian Fruit Bats.

Between the various lagoons, known locally as jheels, were a series of paths were we could see …

… a variety of species such as Eurasian Hoopoe …

… here of the greyer Asian race saturatus

Also seen were Yellow-footed Green Pigeons and Bank Mynas …

… the inevitable Coppersmith Barbets …

… and the personata race of White Wagtail, sometimes known as Masked Wagtail. These breed in the Tien Shan of Kazakhstan unlike the race leucopsis that we saw on the Chambal River that breeds in China.

Also present were a few Citrine Wagtails, wintering from further north in Asia. This is probably an adult female as 1st winters lack the yellow tones.

Bharatpur is famous for its pythons and we found this individual in ditch along side the path, but it was nowhere a big as the one I saw on my 1986 visit which must have been 5m long.

Is this another snake or just a Purple Heron having a preen?

Other species included Pied Stonechat …

… White-cheeked Bulbul …

… Rufous Treepie …

… a roosting Dusky Eagle Owl …

… and a Greater Coucal.

Around the jheels we saw a wide range of waterbirds …

… from familiar ones like Common Kingfisher (the same species that occurs in the UK) …

… to the mush larger White-breasted Kingfisher which has a range from Turkey and the Levant through to SE Asia.. This species used to be known as Smyrna Kingfisher after the ancient city of the same name on the Turkish coast. More recently Symrna has been renamed Izmir.

The species once known as ‘purple gallinule’ has been renamed Swamphen to distinguish it from the bird known as Purple Gallinule in North America. Then it was split into six species with the ones in India becoming Grey-headed Swamphen.

Another inhabitant of these wet grassy meadows was Bronze-winged Jacana, which in spite of appearances is a species of shorebird/wader and not a rail! We only saw a single Pheasant-tailed Jacana which is surprising as they were as common as Bronze-winged on my last visit.

A female and two immature Knob-billed Geese …

… but only the male has the ‘knob bill’. This species has recently been split from the South American version which is now called Comb Duck.

Another species of duck that we saw regularly was the Indian Spot-bill.

We only saw a few Woolly-necked Storks, the Asian race is sometimes treated as a separate species from the one in Africa on the basis of bronze colouration on the wing coverts and paler face.

We only saw a single Black-necked Stork, this compares to a dozen or more that I saw in 1986. In general big wetland birds; cranes, storks and wetland breeding raptors are doing badly in Asia. In 1986 we saw 37 Siberian Cranes at Bhartapur; now the western population of this species, which used to winter here, is reduced to a single individual which winters in Iran. Pallas’ Fish Eagle is another species that used to occur and we saw regularly in 86 but has now vanished.

The male of this species has a black eye whilst the female has a nice golden colour. In spite of losses in India this species has a wide range and its stronghold is probably the wetlands of northern Australia.

Many waterbirds breed on the jheels but at this time of year most are using the trees as roosting sites. In this photo mainly Great Cormorants, Painted Storks and Black-headed Ibis.

A closer view of a pair of Painted Storks with a couple of immatures and two Black-headed Ibis.

And an even closer view of one of the adults.

Of the most obvious feature of the site was the herons, as well as the expected Great, Little and Cattle Egrets there were good numbers of Purple Herons …

… Black-crowned Night Herons …

… and even (after a bit of searching) rarer species like Yellow Bittern …

… and Black Bittern.

Little and Large: The saw three species of cormorant, here are the eponymous Great Cormorant and Little Cormorant. The third one (not shown) breaks the naming convention and goes by the name of Indian Cormorant.

This is not a cormorant but a darter, a different Family comprising of just four species, sometimes known as ‘snake birds’, with one occurring in each of the Australasian, Afrotropical and Oriental regions and another in the Americas. This is, perhaps unsurprisingly, named Oriental Darter.

This darter has got some fishing net caught around its bill, presumably obtained outside the park as no fishing occurs within. The staff were attempting to capture it to remove the netting, I hope they succeeded.

I mentioned in the last post how vulture numbers in India have dropped to <1% of their former numbers due to poisoning with the vetinary drug that we know as Volterol or Diclofenac. One species that has survived better than the others is Egyptian Vulture, whether this is because it can metabolise the drug or feeds less on the poisoned cattle carcasses, I don’t know. This was the only vulture species we saw on the trip.

There were many raptors around the site such as this Western Marsh Harrier, a bird we are familiar with from the UK (you have to go a lot further east than India before you encounter Eastern Marsh Harrier).

Less familiar to us was Crested Serpent Eagle, this bird with the pale forehead and supercillium is an immature …

… whilst this is an adult.

We also saw Greater Spotted Eagle (seen here with two Black Drongos) and an Indian Spotted Eagle. Indian Spotted Eagle has been split from the more westerly Lesser Spotted Eagle and as my recollection of seeing it in 1986 is somewhat vague I was very pleased to catch up with it.

Greater Spotted Eagle can be identified in flight by the larger number of ‘fingers’ in the outer wing but is a bit trickier when perched, the shaggy nape and the gape extending up to but not beyond the centre of the eye are key features. All these large Palearctic eagles used to go by the scientific name of as Aquila clanga. Now for reasons I don’t understand it has been transferred to the new genus Clanga, so its now Clanga clanga! If anyone would ever reverse this decision they would be dropping a clanger!!

We were very pleased to come across a group of five Grey-headed Lapwing (three of which are pictured here), a species I’ve several times before in Asia but never as far west as this.

‘All the Birds of the World’ the single volume from Lynx Edicions which illustrates every bird in the world shows 24 species of Vanellus plover of which Grey-headed of course is one. One of the 24 is almost certainly extinct but I’m glad to say I’ve seen all but one of the others (Brown-chested, which I missed in Uganda).

Another Vanellus plover, Red-wattled Lapwing in the background and a Common Moorhen to the left but the star of this photo is the impressively named Indian Narrow-headed Softshell Turtle.

On our last morning we sort out some birds that skulked in the vegetation that fringed the jheels, these Pied Mynas were easy enough to see …

… as were Black Redstarts (here a female of one of the red-breasted Central Asia races).

Wintering birds from Siberia included Bluethroat …

… but best of all was this superb Siberian Rubythroat that entertained us for some time, recalling seeing that one at Osmington Mills in Dorset in 1997, (a sighting so remarkable that some still claim it was an escape from captivity)

Unlike Tadoba, the previous national park we visited, Bharatpur doesn’t have any dangerous wildlife (hence all the tourists travelling around on bikes or rickshaws) but we did hear there was a Leopard in one (closed off) area. However we did see a few mammals such Rhesus Macaque …

… which scanned the tourists carefully for any sign of a free meal …

… several Golden Jackals were seen …

… a female Nilgai (with Purple Heron) …

… Indian Grey Mongoose …

… the inevitable Palm Squirrel …

… and Wild Boar.

I’m sure if we had spent more time at Bharatpur we could have seen more species in this wonderful park but we had to move on this time to the city of Jaipur. There was a site on route where the rare Indian Spotted Creeper, a life bird for me, could be found. Wild About Travel had arranged for our guide Gaj to accompany us and see if he could find the creeper. Unfortunately the creeper wasn’t at home but we did see a few other quality birds.

The next post will be about our visit to the historic city of Jaipur.

In November 2020 we went on a customised tour of northern India organised by Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel

This was Margaret’s first visit to India (although my sixth) and allowed us to combine visits to cultural sites with wildlife viewing. Earlier posts on this tour dealt with our visits to Tabora National Park and the Chambal River area.

This is the third post on our trip to India in November 2019 and covers our visit to the Taj Mahal and the ancient city of Fatehpur Sikri in the city of Agra which we visited on route to our next overnight stop in the city of Bharatpur.

We left the Chambal River Lodge mid-morning and drove to Agra. Most of our earlier travels, from Nagpur to Tadoba and back, had been on main roads and the journey from Agra to Chambal was before dawn, so this was Margaret’s first real experience of the vibrancy and colour of everyday Indian rural life.

… to the omnipresent cows and water buffalos.

A few birds were seen on route such as the suitably common Common Babbler.

On arriving we arranged a local guide and took a bicycle rickshaw from the car park …

… travelling to the entrance to the Taj Mahal in style.

Our guide made sure we paused for all the clichéd photos.

To say the Taj Mahal was crowded would be an understatement.

This is probably the best and most awe inspiring view of the Taj Mahal and as can be seen from all the phones and selfie sticks, everyone else felt the same.

From Wikipedia: The Taj Mahal is an ivory-white marble mausoleum on the southern bank of the river Yamuna in the Indian city of Agra. It was commissioned in 1632 by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (reigned from 1628 to 1658) to house the tomb of his favourite wife, Mumtaz Mahal; it also houses the tomb of Shah Jahan himself. The tomb is the centrepiece of a 17-hectare complex, which includes a mosque and a guest house, and is set in formal gardens bounded on three sides by a crenellated wall. Construction of the mausoleum was essentially completed in 1643, but work continued on other phases of the project for another 10 years. The Taj Mahal complex is believed to have been completed in its entirety in 1653 at a cost estimated at the time to be around 32 million rupees, which in 2020 would be approximately 70 billion rupees. The construction project employed some 20,000 artisans under the guidance of a board of architects led by the court architect to the emperor, Ustad Ahmad Lahauri. The Taj Mahal was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983 for being “the jewel of Muslim art in India and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world’s heritage”. It is regarded by many as the best example of Mughal architecture and a symbol of India’s rich history. The Taj Mahal attracts 7–8 million visitors a year and in 2007, it was declared a winner of the New 7 Wonders of the World (2000–2007) initiative.

One bird that was absolutely abundant on my first visit to India in 1986 was Black Kite. I was surprised how few I saw on this trip, however there were quite a few flying around the dome of the Taj Mahal.

The race here is govinda, a more strongly marked race than those in Europe.

These black inlays in the white marble produce an optical illusion because if you gaze upwards the zig-zags become a straight line. I tried to capture this in a photo but the pillars ‘fell over backwards’ so badly that you will just have to imagine it!

The mausoleum itself is flanked on three sides by these red stone buildings, one of which is the entrance and exit …

… whilst the fourth side is flanked by the Yamuna river.

When I visited the Taj Mahal in 1986 this area was full of vultures, but the widespread use of the veterinary drug diclofenac (used to treat cattle which after death are eaten by vultures) has resulted in widespread poisoning and a reduction in numbers of over 99%. At least there were plenty of Great Cormorants and a few Painted Storks, Ruddy Shelducks and Grey Herons present.

We entered the mausoleum, but there was a policy of no photography inside …

… the tomb of Shah Jahan’s wife Mumtaz Mahal lies centrally and so looks down the the central axis of the complex. Shah Jahan’s tomb which was placed here after his death in 1666 lies offset to one side. As I was unable to photograph the tomb I’ve copied this wide-angle shot from here

As we emerged from the mausoleum it was clear that the compound was rapidly filling up with tourists, it was time to get some lunch and move on.

We continued on to the ancient city of Fatehpur Sikri.

From Wikipedia: Fatehpur Sikri is a city in the Agra District of Uttar Pradesh, India. The city itself was founded as the capital of Mughal Empire in 1571 by Emperor Akbar, serving this role from 1571 to 1585, when Akbar abandoned it due to a campaign in Punjab and was later completely abandoned in 1610. The name of the city is derived from the village called Sikri which occupied the spot before. An Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) excavation from 1999 to 2000 indicated that there was a habitation, temples and commercial centres here before Akbar built his capital. The region was settled by Sungas following their expansion. In 12th century, it was briefly controlled by Sikarwar Rajputs. The khanqah of Sheikh Salim existed earlier at this place. Akbar’s son Jahangir was born at the village of Sikri in 1569 and that year Akbar began construction of a religious compound to commemorate the Sheikh who had predicted the birth. After Jahangir’s second birthday, he began the construction of a walled city and imperial palace here. The city came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri, the “City of Victory”, after Akbar’s victorious Gujarat campaign in 1573. After occupying Agra in 1803, the English established an administrative centre here and it remained so until 1850. In 1815, the Marquess of Hastings ordered repair of monuments at Sikri.

Again from Wikipedia: The city was founded in 1571 and was named after the village of Sikri which occupied the spot before. The Buland Darwaza was built in honour of his successful campaign in Gujarat, when the city came to be known as Fatehpur Sikri – “The City of Victory”. It was abandoned by Akbar in 1585 when he went to fight a campaign in Punjab. It was later completely abandoned by 1610. The reason for its abandonment is usually given as the failure of the water supply, though Akbar’s loss of interest may also have been the reason since it was built solely on his whim.[14] Ralph Fitch described it as such, “Agra and Fatehpore Sikri are two very great cities, either of them much greater than London, and very populous. Between Agra and Fatehpore are 12 miles (Kos) and all the way is a market of victuals and other things, as full as though a man were still in a town, and so many people as if a man were in a market.

This lady looks impressed by the architecture!

Of course we could only visit a small part of the city. More from Wikipedia: Fatehpur Sikri sits on rocky ridge, 3 kilometres in length and 1 km wide and palace city is surrounded by a 6 km wall on three sides with the fourth bordered by a lake. The city is generally organized around this 40 m high ridge, and falls roughly into the shape of a rhombus. The general layout of the ground structures, especially the “continuous and compact pattern of gardens and services and facilities” that characterized the city leads urban archaeologists to conclude that Fatehpur Sikri was built primarily to afford leisure and luxury to its famous residents. The dynastic architecture of Fatehpur Sikri was modelled on Timurid forms and styles. The city was built massively and preferably with red sandstone. Gujarati influences are also seen in its architectural vocabulary and décor of the palaces of Fatehpur Sikri. The city’s architecture reflects both the Hindu and Muslim form of domestic architecture popular in India at the time. The remarkable preservation of these original spaces allows modern archaeologists to reconstruct scenes of Mughal court life, and to better understand the hierarchy of the city’s royal and noble residents. It is accessed through gates along the 8.0 km long fort wall, namely, Delhi Gate, the Lal Gate, the Agra Gate and Birbal’s Gate, Chandanpal Gate, The Gwalior Gate, the Tehra Gate, the Chor Gate, and the Ajmeri Gate. The palace contains summer palace and winter palace for Queen Jodha.

One thing that greatly surprised Margaret was that pretty young Indian ladies would ask if they could take a selfie with her, like she was some sort of celebrity. I caught these two in a more candid pose after they had done the selfie thing with my wife.

We appreciated that we had only visited of this ancient place but were pleased we had taken the time to do so. In spite of the constant haze and pollution that blights the lowlands of northern India in the winter we had captured some nice photos …

… however as always we concentrated on photographing what we came to see rather than photographing us!

Rose-ringed Parakeets (or Ring-necked as they are often called in the UK) were a common sight …

… native to India and parts of northern Africa this species has been introduced into many places, including the UK where they often become a pest, competing with native species for food and nest holes.

Northern Palm Squirrels were a common sight running along the ancient walls and roofs.

A few final views of Fatehpur Sikri …

… its lakes …

… and spires …

… before we departed to the city of Bharatpur and the wonderful wildlife reserve nearby.

On route we driven down a major highway, this gave Margaret her first chance to experience heavy Indian traffic. I don’t think she sat in the front seat again after that! Although Indians nominally drive on the left like we do in the UK, the rules of the road seem to be made up as they go along. Of course the traffic speed is much lower than the UK, with all the cows, sheep, bicycles and vehicles going the wrong way it couldn’t be otherwise. We loved the highly decorated Indian lorries, although not their kamikaze driving.

The next post will cover our visit to one of the finest wetland reserves in the world, Keolandeo National Park, known also universally by the name of the adjacent city Bharatpur.

This is the second post about our private trip to India in November 2019 which was organised by Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel

The previous post dealt with our time at Tadoba National Park and our overnight train journey from Nagpur to Agra. Arriving at Agra at 0500. We were met by our driver who took us to the Chambal River Lodge to the east of the city where we stayed for one night.

We arrived at dawn and after breakfast I decided to have a look around the grounds while it was still cool. Margaret, feeling very tired after our overnight train journey opted for a rest.

Indian Peacocks were ubiquitous and noisy …

… and garrulous groups of Jungle Babblers fed in the ornamental hedges and open areas.

Northern Palm Squirrels were easy to find …

… and Common Mynas lived up to their name. This omnivorous and adaptable species has a wide range in southern Asia but regrettably has been introduced to places like Australia, New Zealand, parts of the USA, South Africa and many islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans where it has done untold damage to native species.

Also around the gardens were these Ashy Prinias …

… and in deep cover I came across a Golden Jackal.

Although of course you see more when accompanied by a local guide, it was fun to spend that morning finding my own birds, which included Greenish Warbler, Pied Starling and this Coppersmith Barbet.

We spent the afternoon on the Chambal River, the reason for our visit with local guide Gajendra, photos of which are shown below. On the second morning he took us around the gardens again and also outside the lodge into the surrounding countryside. Here we came across a wider range of species including – Verditer Flycatcher …

… a roost of Indian Flying Foxes (or Indian Fruit Bats) …

… Common Tailorbird, so called because it sews leaves together to make a nest …

… roosting Spotted Owlets …

… and Indian Scops Owl.

More species awaited us outside the walled gardens …

Here we saw a new range of open country species like Black-breasted and Baya Weavers, Red-headed Buntings from Central Asia and good numbers of Brahminy Mynas (pictured above).

Other species included Yellow-footed Green Pigeon, one of the easiest to see of the 30 species in the genus Treron which occur from Africa east to to Wallacea.

Also seen were Brown-headed Barbet …

… Indian Rollers …

… and the distinctive Siberian race tristis of Common Chiffchaff which surely deserves specific status.

At Tadoba langurs had been the common monkey species, here Rhesus Macaques abounded.

Wet areas held White-breasted Waterhens …

… whilst Red-wattled Lapwings …

… and Greater Coucals (a species of cuckoo) could be found at the field edges.

In general I approve of most taxonomic splits, the insights provided by genetic and acoustic research has shown that there are more ‘good species’ than examination of museum specimens alone ever could. However there is one recent split that I feel uncomfortable with, the apparently arbitrary division of Cattle Egret into Eastern and Western. This non-breeding Eastern Cattle Egret looks the same as the Western ones we see in Europe. Colour of the plumage in breeding plumage is supposed to be the clincher but I have seen breeding Westerns in the Caribbean as orange-tinged as breeding Easterns are supposed to be. It is claimed that there is a difference in vocalisations but others have disputed this and said that the comparison has been made between non-homologous calls.

We spent the afternoon of the first day on the nearby Chambal River. A bridge is being built across the river …

… but until it is complete locals will have to depend on overcrowded ferries.

We set off in a boat like this, initially it was quite overcast but as the afternoon progressed the murk cleared. The Chambal is a tributary of the Yamuna River, which itself is a tributary of the Ganges.

Among the many species we saw from the boat were River Lapwings …

… wintering Desert Wheatear …

… here showing the diagnostic all black tail.

Ruddy Shelducks here for the wintering from their north Asian breeding grounds …

Joined by Mongolian/Tibetan Bar-headed Geese which fly over the high Himalayan peaks to reach their wintering grounds.

A couple of imposing Great Thick-knees, a species of stone-curlew, were seen on the bank …

… as were Sand Lark, a species closely related to Lesser Short-toed Lark (which has recently been renamed Mediterranean ST Lark following the splitting off of Turkestan ST Lark). Note that some primary tips can be seen beyond the tertials, an important feature to distinguish members of this group from Greater ST Lark.

The black-and-white wagtails are a confusing group, White Wagtail, here of the race leucopsis which breeds in mainly in China, can be seen along with race personata from central Asia and possibly other Asian races as well. All these races are of the same species as our familiar yarrelli Pied Wagtails in Britain. Add to that the marked variation between 1st winters/adults and and males/females and the situation gets most complex.

On the other hand the resident White-browed Wagtail are considered a separate species …

… and we had close up views of several along the river.

Non-avian highlights included this large and comparatively aggressive crocodilian – the Muggar …

… and the bizarre yet benign Gharial …

… this crocodilian is exclusively a fish eater and its long snout and 110 pairs of interlocking teeth are adaptions to enable this. Now occurring in only 2% of its historic range and is now considered critically endangered.

Another reptile we saw was the Indian Roofed Turtle.

Asian ‘big river’ birds are in trouble, the enigmatic White-eyed River Martin of Thailand apparently went extinct as soon as it was discovered, Indian Skimmers and Black-bellied Terns are seldom seen and we didn’t encounter them on this trip. Pollution, mineral extraction and disturbance have taken their toll. Fortunately this section of the Chambal River is a reserve and lets hope it will protect these birds for future generations.

The next post will cover our visit to the tourist hotspots of the Taj Mahal and Fatehpur Sikri in Agra.

Although Margaret likes to travel she usually doesn’t want to join me on long and intensive birding trips where most of the time will be spent in dense forest. However we have enjoyed trips to Europe, the USA, South Africa and the Middle East where birding is mixed with sightseeing and other activities.

One area she was keen to visit was India. I have been on four dedicated birding tours of India plus have visited Bhutan and Sri Lanka so I’ve most of the birds, but there were still a few things I wanted to see. We needed some form of organised trip as I had absolutely no desire to drive myself, but both a standard tourist trip with no wildlife or a intensive birding trip with no sightseeing were out of the question. It was suggestedwe contact Jo Thomas of Wild About Travel who was able to organise an itinerary around what we wanted to see, with drivers, hotels, transfers etc all for a quite reasonable price. In particular she arranged us to visit Tadoba National Park in the state of Maharashtra which a park that I knew nothing about, yet proved to be highly successful and a beautiful place to visit.

This post is mainly about our visit to Tadoba National Park.

When I visited India for the first time in 1986 Delhi airport was a shabby affair, hot, crowded and inefficient – it lived up to the western stereotype of India. Now look at it, modern, air conditioned and efficient. We had decided not to burn the candles at both end on this trip so after the overnight flight we transferred to a nearby hotel where we rested for much of the day before being picked up and taken to the domestic terminal for an evening flight to Nagpur. Here we were driven to another hotel and the following morning were collected for the three-hour drive to Tadoba National Park.

Tadoba Nation park consists of 578 sq km of mainly teak forest, grassland and marshes in central Maharashtra. There are about four lodges around the periphery and we stayed at Jaharana Jungle Lodge. In the afternoon we made the first of four safaris in open backed jeeps. It was magical driving though the tall teak forest with peacocks and other birds scampering across the tracks.

Although there were plenty of birds to see in Tadoba, for safety reasons we were not allowed to leave the jeeps except at one or two designated areas. In reality mammals were the main focus here. The first mammal species to be seen was this Grey Mongoose.

Tadoba has recently acquired a large buffer zone around the park, significantly increasing its area. This consists of mainly open grassland and was very good for seeing ungulates, in particular the impressive Gaur.

Zooming in you can see just how large and imposing a bull Gaur is, the head and body (excluding tail) measure around 3m and it can be over 2m tall at the shoulders. It is the largest wild bovid extant today. I have longed to see this species since childhood and in 2018 I finally succeeded. After quite some effort we saw a few cows and calves in dense forest in southern India. I was amazed how common and easy they were to see in Tadoba and how conspicuous the bulls were.

Another common inhabitant of the more open areas were Nilgai, mainly herds of hinds and calves.

Indeed some would run down the track ahead of the jeep before heading of into cover.

The male Nilgai is often known as the ‘Blue Bull’ but of course its an antelope not a bovid. After the two species of Eland in Africa its probably the largest of the antelopes.

Sambar were commoner in the wooded areas and hinds were regularly seen from the tracks, this species is similar in size or a bit larger than a Red Deer.

This impressive stag has just enjoyed a wallow in the mud.

Chital, sometimes called Spotted Deer, were common in shaded glades where the forest met open areas of pasture. I suppose their spots camouflage them well in this sort of habitat.

It was lovely to see this Chital fawn suckling but it would have been a better photo if mum had turned her head towards us!

Unlike our similarly spotted Fallow Deer, Chital don’t have palmate antlers.

Langur Monkeys (more precisely Northern Plains Grey Langurs) were common.

They seem to have a feeding association with the Chital (although there is another explanation for their co-habitation) which I will explain later.

As evening fell we made our way back and came across this huge bull Gaur by the road. Bear in mind I’m standing up on the back of the jeep. If I was at ground level it would be towering over me!

There were plenty of birds to see both around the lodge and on the game drives. Here is the ubiquitous Spotted Dove.

Peacocks are thought of as ornamental birds, commensal with mankind but in the forests of India they are truly wild. The mating season was over though and the males had dropped their spectacular tail feathers.

Red-wattled Lapwings were common throughout the trip.

This one was nesting on a raised embankment so when we stopped briefly for a photo it was at eye level.

India , like much of the Oriental region, has some great woodpeckers including this Black-rumped Flameback.

There were a number of wintering pipits but this one seems to be the resident Paddyfield Pipit, rather than its slightly larger and migratory cousin Richard’s Pipit.

The area was also home to a male Pied Stonechat …

… and the eponymous White-eyed Buzzard.

There were a few wetland areas but getting close enough for decent photos wasn’t easy as we were confined to the jeep but I quite like this shot of an Oriental Darter drying its wings. Darters and their cousins the cormorants don’t produce oil from their preen gland to waterproof their feathers. This means they lack buoyancy underwater and so can swim faster, deeper and for longer when hunting fish but the downside is that they must hang their wings out to dry when they surface.

Another bird that showed well along the same lake was Red-naped Ibis, a bird that I missed on visits to India up until 2018 when I finally caught up with them in Rajasthan.

Not such a great photo, as it was hiding in thick vegetation, but this was the only Lesser Adjutant (stork) of the trip.

Green Bee-eaters, here of the race orientalis, which is rightly given specific race by some authorities, was common in the park with hundreds seen.

Of course the animal most tourists want to see is the Tiger. The establishing of Tiger reserves all over India has probably saved the species from extinction, but it is still heavily targeted by poachers for the Oriental traditional medicine trade. Almost all tourists head off in the early morning, there are lovely views like this as the sun filters through the dust stirred up by the jeeps. Communication between vehicle by phone or radio is banned, presumably to avoid every one racing around after Tiger sightings, but these still happen. After a number of false alarms our lucky break came (twice) on the second afternoon.

The presence of a Tiger is often revealed by the bark of a Chital …

… or the chatter of Langurs, some of which which remain alert in the trees and so can see danger coming. The Chital, on the other hand, probably have a better sense of smell, this symbiosis seems to benefit all but the Tiger!

We had two sightings of Tiger that afternoon, this was the second and probably least successful of the two, hence the decision to keep the best for last. It was a well known male; magnificent, but for most of the time it was hidden deep in cover.

There were two other jeeps ahead of us and they reversed to give the Tiger some space when it decided to wander down the road. The light was already going and this wasn’t such a good encounter as the earlier one.

Earlier that afternoon we had taken a one-way side road that led up to a viewpoint over a lake when another jeep passed and said there was a Tiger not too far away. To my surprise the driver didn’t either continue and go the long way round or ignore the one-way regulation and turn about, instead he reversed for over a mile as fast as he could. By the time we reached the main road there were about four jeeps all in a convoy and all going backwards! We joined an assemblage of at least six other jeeps and stared into the dense roadside vegetation.

Although initially hidden it wasn’t long until this female walked out right into the open …

… ignoring the admiring hoards she sauntered past the jeeps a matter of feet away.

It goes without saying that if she had wanted to she could have leaped into any of the jeeps in one bound and attacked anyone of us. Given the fact that a birder I once knew was killed by a Tiger back in the 80s, this was not something to be dismissed lightly.

I don’t mean this to sound patronising so don’t take it that way, but in National Parks in Africa almost all the visitors are western tourists. You hardly ever see a local unless they are employed there. So I was delighted to see that out of the 40 or so tourists (in 15 vehicles by the time we left!) who were watching the Tiger we were the only Europeans. Only when people value the wildlife in their own country will true progress be made in conservation.

I think this lad had the wrong hat on!

The Tiger (or should I say Tigress) sat down just feet from the jeeps. One guy decided to straddle two vehicles and I ended up trying photograph her through his legs.

I make no apology for posting so may photos of the same animal. I had a poor view of a Tiger from our bus in Corbett NP in 1986 and one quickly crossed the road just in front of our Jeep in Kaziranga in Assam in 2001 but both were brief encounters. This Tiger just hung around giving fantastic views, one of my best wildlife encounters ever.

In due course she crossed the road behind us and lay down on this rock and was still there when we eventually left. As I said and illustrated earlier in this post, a couple of hours later that afternoon we had another encounter – this time with a male.

So with two Tigers under the belt we drove back to the lodge at dusk. But the day still had a surprise in store. A Sloth Bear walked out onto the track in front of us!

… and moments later was joined by a second. I had seen Tiger before but this species was new to me. ten years previously I hadn’t seen a single species of bear in the wild, then I saw Polar Bear in Spitsbergen in 2011, Black Bear in USA in 2014, Brown Bear in Kamchatka in 2016. Just three more to go! The only trouble was it was getting very late for photos and these were taken at quite low shutter speeds.

Back at the lodge we were intercepted on our way from the chalet to the dining room and directed towards the swimming pool. We were treated to a poolside dinner. Romantic, but when the waiter stood in front of the bright light you couldn’t see what you were eating.

Our final morning at Tadoba brought us some new birds but no new mammals. Having said that I’ve now seen most of the ‘good’ mammals in lowland India. All those marvels that I read about in Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book as a child and have yearned to see ever since have been put to bed. We were picked up late morning and driven back to Nagpur, this time to the railway station. We got there quite early and had to hang around for a couple of hours, but we did add one more species to the mammal list whilst waiting – Brown Rat!

It had been arranged for us to take the overnight train to Agra, we shared a first class compartment with two locals. It was quite comfy but the movement of the train as it went over points and juddered to a stop at stations throughout the night meant we got little sleep. We were on the train for about 12 hours and arrived at Agra around 0500 where we were met by by our driver for the next section of the trip.

I don’t want to end this blog post with a photo of a railway compartment so here’s the star of the show (yet) again.

The next post will illustrate our time on the Chambal River and a visit to one of the most famous buildings in the world, the incomparable Taj Mahal.

This is the second post covering my trip to the South Moluccan islands of eastern Indonesia.

In the first post I explained that the Moluccas weren’t connected to mainland Asia in the Ice Ages whilst the Greater Sunda islands of Borneo, Sumatra, Java and Bali were, nor were they connected to Australia like New Guinea and the Aru Islands were. As a result there has been limited mixing of Asia and Australian birds and what mixing there has been was within the area known as Wallacea, shown within the dotted line below. For a map of Indonesia’s coast line during the height of the Ice Age see part one of my account of the trip to the South Moluccas.

As I outlined in the previous post, the group of Indonesian islands that were not connected to either Asia or Australasia during the Ice Ages are known as Wallacea in honour of Alfred Russell Wallace, the co-discovered (with Charles Darwin) of evolution via natural selection, who was the first to speculate on the unusual mix of Australasian and Asia species in this region.